In The BeginningChristian witness may have taken place on this site since Roman times. The first church was built soon after 971 AD and dedicated to the memory of Swithin, Bishop of Winchester from 852 to 862. The foundations of this Saxon church lie beneath the floor of the crypt.

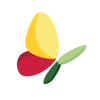

In medieval times Walcot was a hamlet outside the walls of Bath, but was taken within the enlarged city boundary in 1590.

The Saxon church was badly damaged by storms in 1739. John Wood, the architect who led the astonishing expansion of Bath in the mid-18th Century, put forward plans for a replacement, but a design by the then Churchwarden, Robert Smith, was selected instead. This church, completed in 1742, was soon swamped by the rapid growth of Georgian Bath’s elegant ‘Upper Town’, and John Palmer (architect of Lansdown Crescent) was commissioned to build a new one.

|

A New ChurchPalmer’s new church was consecrated in 1777. Within ten years it also became too small, and Palmer extended it eastwards by two bays. A classical spire, added in 1790 to the existing tower, completed his design. St Swithin’s became the parish church of Georgian Bath. Today it is the only remaining 18th Century parish church in the city.

During the 19th Century the rich and famous worshipped here. Many of them are commemorated by memorials inside the church. The space for burials ran out, a new cemetery was opened on Lansdown in 1848 on land attached to William Beckford’s tower, which was conveyed to the then Rector by Beckford’s daughter, the Duchess of Hamilton.

In the Victorian era St Saviour’s, St Stephen’s, Holy Trinity and St Andrew’s were built as daughter churches to accommodate the growing population of the parish. All except the last eventually became independent parishes. The present-day parish extends from Royal Crescent in the west to Snow Hill in the east.

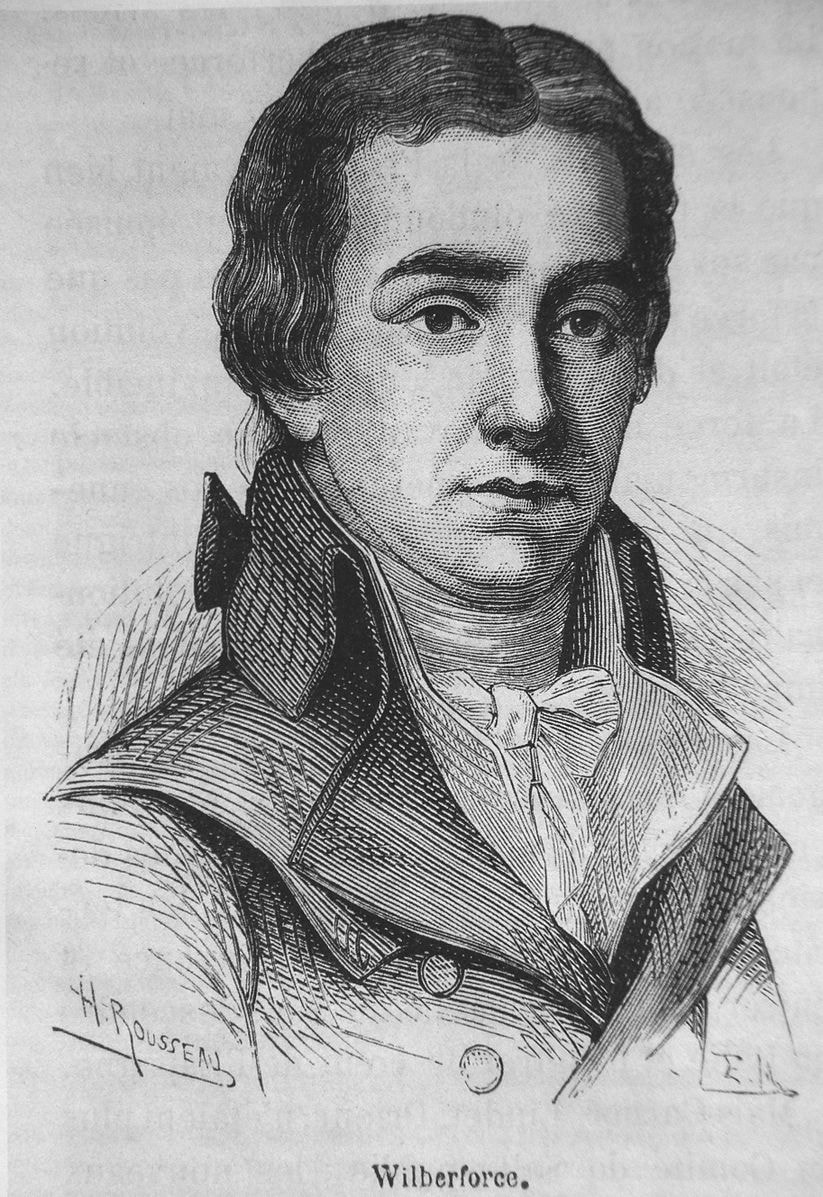

We hope you will come and explore the amazing collection of marble wall monuments in St Swithin’s, which might be said to be the main Georgian feature of the interior. As the Pevsner Architectural Guide for Bath notes, “innumerable monuments… urns in particular are many.”

|

Under Christ's InfluenceIn the 1840s a stained glass window depicting the Ascension was inserted in the east wall.

In 1881 a landslip destroyed 175 houses opposite the church (where Hedgemead Park is now). The church building suffered too and had to be strengthened. In 1891 the east end was re-ordered in line with contemporary thinking about church design. Most of these alterations disappeared in subsequent refurbishments, except for the shallow sanctuary which projects discreetly over Walcot Street.

In 1958 a programme of changes included a new east window to replace the one blown out during the bombing of Bath in 1942. The replacement window maintains the Ascension theme, with the church itself depicted at the feet of Christ.

The exterior of the church was cleaned and repaired in the 1990s. Major restoration of the interior in 2008/9 provided a light, airy worship space which respects Palmer’s original designs, linked by a new staircase to the fully redeveloped crypt. Together they form the hub for continuing Christian witness to the local community.

“Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith.”

Hebrews 12:1-2 |

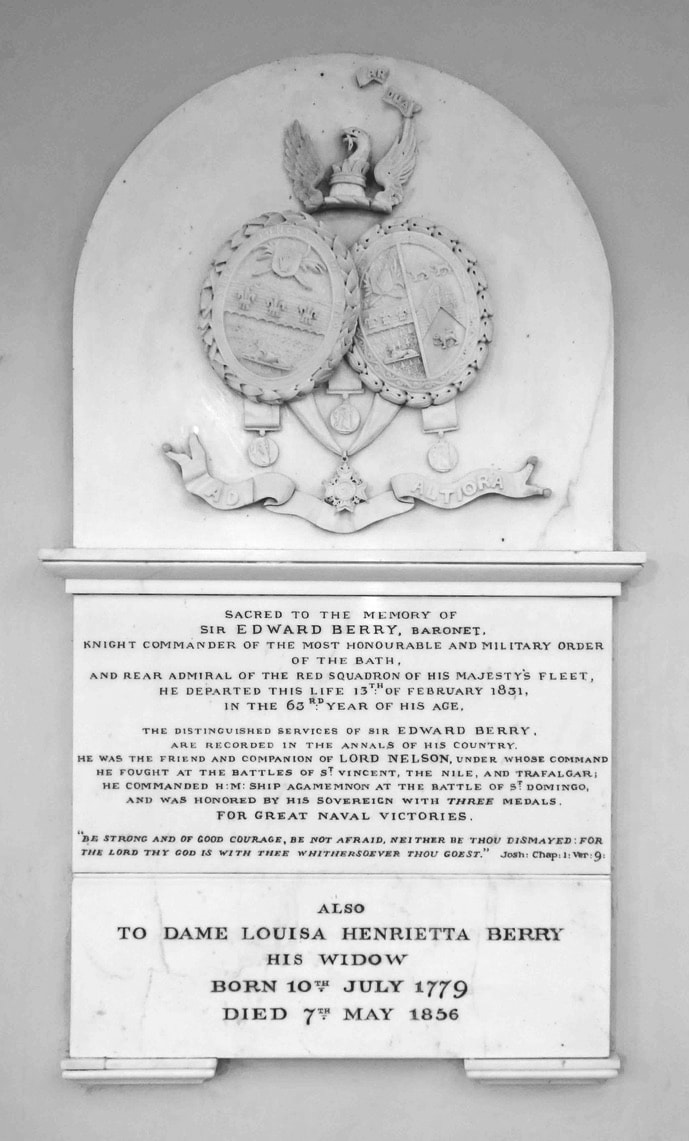

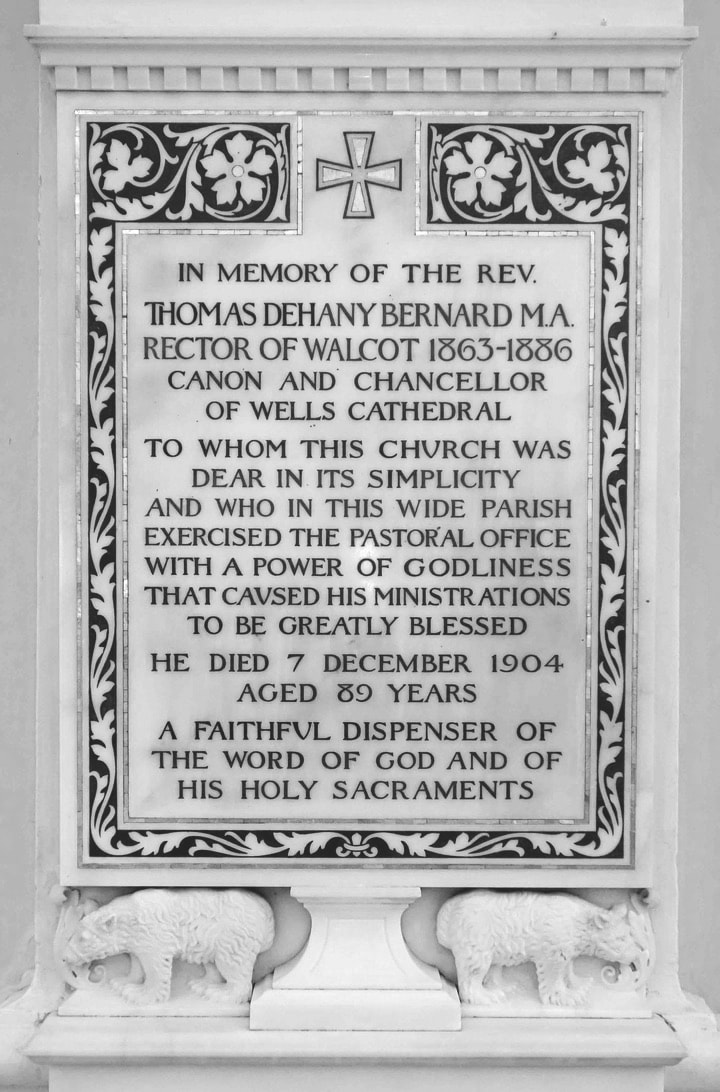

Monuments Rich In HistoryThe monuments range in style from late Baroque (heavy design with multi-coloured marbles) eg Paul Bertrand, fashionable jeweller (1688-1755); to a more restrained white-on-black classical format, eg Jenny Prideaux (1734-1819), wealthy widow and benefactress. There is a later group with beautiful mosaic inlays, eg Rev Thomas Dehany Bernard, Rector of Walcot (1815-1904) and the two World War 1 memorials.

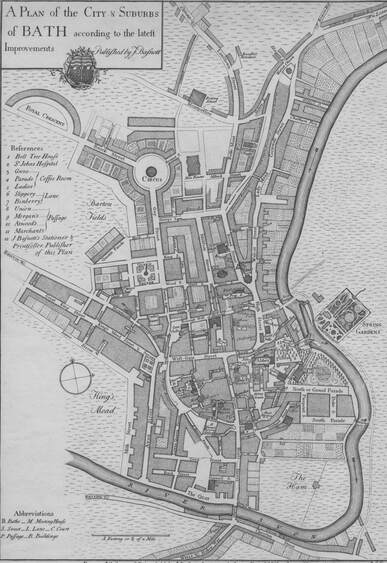

The people memorialised are drawn from the well-off middle class of the day: army and naval officers, administrators of the East India Company, plantation owners in the West Indies, lawyers, Members of Parliament, business people and clergy. They are the sort of people you find in Jane Austen’s novels, and as a Bath resident herself in the 1800s she may have known some of them.

Stories behind the memorials include the naval tragedy in which Lieut James Lewis Fitzgerald and several others died in 1835; the widow and three small children left behind by William Potter, organist of the church in 1805, where the monument displays as symbols of mortality a lyre with broken strings, an hourglass with wings and a blank scroll; and Catherine Uhthoff, who came home wet from a walk in 1790, stood so close to the fire to warm up that her dress caught alight and, despite her sister rolling her in the rug to put out the flames, died next day from her injuries.

As well as recording the people, the memorials testify to the faith in God which members of St Swithin’s have shared over the centuries and which continues to be so important in the church today. There are many touching epitaphs and uplifting scriptural quotations, largely from the Letters in the New Testament.

|

Remarkable PeopleThere are 163 monuments in the main part of the church, most of which date from the 1760s to the 1840s, with another 30 in the crypt. Some of the most prominent people memorialised are:

William Hoare RA, (1708-1792), portrait painter of high society and royalty.

Fanny Burney (1752-1840), the novelist, contemporary of Jane Austen, author of Evelina and other satirical novels.

Sir Edward Berry (1768-1831), Rear Admiral, Nelson’s right-hand man at several engagements including Trafalgar, and the only officer in the fleet to be awarded three gold medals.

Jerry Pierce FRS, (1695-1768), leading surgeon and colleague of Dr Oliver at the Mineral Water Hospital.

Christopher Anstey (1725-1805), writer and poet, author of the must-read book for 18th Century visitors, the New Bath Guide.

John Palmer (1738-1817), architect of St Swithin’s and many other Bath landmarks, including Lansdown Crescent, St James’s Square, Christchurch and the Pump Room.

Thomas Pownall (1722-1805), also known as Governor Pownall. Colonial administrator and pre-Revolutionary governor of New Jersey, Massachusetts Bay and South Carolina. Strong advocate of the rights of the American settlers.

You can find further information and articles on specific people further down this page.

|

Further InformationA Personal View of the Monuments in St Swithin's. This personal view of the monuments and the background to them is based on a talk given by Henry Brown in the church to the History of Bath Research Group in May 2019

Naval and Marine Officers. A document listing and detailing monuments dedicated to Naval and Marine officers.

Jeremiah ‘Jerry’ Peirce F.R.S (1696-1768). An article by Stephen Bird about Jerry Peirce, a prominent member of society in eighteenth-century Bath and the city’s most eminent surgeon.

Sir Edward Berry, Baronet, KCB, 2018. Illustrated biography by Donatella Gelati, a friend of St Swithin’s. For copyright reasons, the author has requested readers not to print copies off.

Thomas Hustler Esq. (1738/9-1802). An article by Stephen Bird about Thomas Hustler, who's monument can be found in St Swithin's Church.

St Swithin’s Church, Walcot, Bath. Internal Memorials, 2014. Report by Dr PJ Bendall, a local historian, with biographical information for each monument.

If you are seeking information about people buried at St Swithin’s or any of the other churches and cemeteries in Bath, please refer to the Bath Burial Index, also compiled by Dr PJ Bendall.

St Swithin’s monuments elements, 2018. A summary spreadsheet of key information about the monuments.

For a more formal summary, see 'Bath' by Michael Forsyth, Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press 2003.

|

Burial Records

|

The parish of Walcot has a number of graveyards. There is the area around St Swithin’s Church, a graveyard with a mortuary chapel at Walcot Gate, Lansdown Cemetery (from 1848 - about 7,000 burials) and part of Locksbrook cemetery (from 1864 - about 30,000 burials).

The graveyard at Walcot Gate must have had a large number of graves, the number of entries in the burial register suggesting that over 20,000 were buried. However, the area was cleared with the remains being reburied at Haycombe cemetery and the surviving 320 memorials placed in rows by the mortuary chapel. The inscriptions were documented in 1981 by David L Houldridge but represent only a small fraction of those buried.

|

If you are looking for a particular record, the Bath Record Office online search facility is very helpful.

Bath Record Office located at the Guildhall has microfiches of the parish’s registers for: baptisms 1691-1884, marriages 1728-1971 and burials 1711-1955 as well as transcripts and indexes. It also has for the parish Alphabetical list of memorials and gravestones in church premises (names only); Inscriptions in Graveyard, by David L Houldridge, 1981 (54 records) and Plan of Gravestones in the Crypt (poor legibility).

|

St Swithin's Church office has a name index for Lansdown Cemetery, which gives the location of the graves as well as maps of the whole cemetery and the individual sections.

From 1864 many inhabitants of the parish were buried in Locksbrook Cemetery, which served Walcot, Weston and St Saviour’s. Burials in that cemetery are not recorded in the parish’s burial register. Bath & North East Somerset Council has a chargeable service for finding a grave in this cemetery.

|